In the wake of the April 16 tragedy, several issues were identified relating to the ability of educational institutions operating in open campus environments to protect their constituents while maintaining a balance between safety and openness. From a technology perspective, the available solutions (e.g., electronic notification systems) provide only bits and pieces of the solution. While many legal and social aspects of this issue need to be taken into consideration, the problem must be addressed primarily by involving all campus constituents including students, staff, administrators, law enforcement personnel, and first responders, along with existing software-based systems used to facilitate situational awareness, security control, and emergency response on campuses.

When one navigates the literature related to campus safety and security, the obvious conclusion is the diversity of expertise that enables addressing this issue from various perspectives. For instance, the field of situational awareness is rich with theoretical and practical solutions to achieving a common operating picture in both closed and open environments. Moreover, current surveillance technologies can provide ways for real-time situation monitoring in various contexts. In addition, there is concrete practical and theoretical work in the area of emergency response management in the case of disasters that provides guidance for managing teams and resources during an emergency. More importantly, from a software engineering viewpoint, service orientation has given rise to the connectedness of more remote and heterogeneous communities of interest than ever before. All this exists while there is a lack of a comprehensive approach that leverages these capabilities to provide a network-centric solution for situational awareness, security control, and emergency response management in an open campus environment. To address this problem, we view it from three different prisms and propose a solution that addresses all facets of the problem in a comprehensive manner.

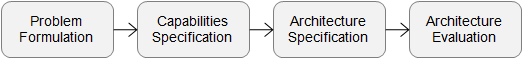

Figure 1 shows the four phases of our research. The ultimate goal of this work is to develop an architecture for a DSS that will address the issue of balancing safety and openness on campuses. To do so, however, we need to understand what it is that we plan to architect. For this purpose, we need to formulate the problem concisely taking into consideration social and legal constraints, and elicit the functional and quality needs that will guide the architecting process. Therefore, our approach consists primarily of:

Figure 1: Research phases

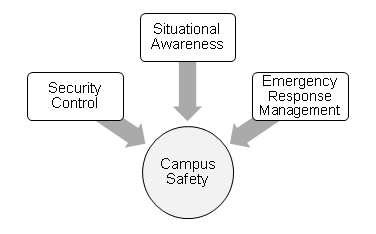

What it means to be safe in an open campus differs from one institution to another, from one administrator to another, and from one law enforcement agency to another. However, commonalities exist across these differences. Figure 2 illustrates how we formulate this problem based on the study of the Virginia Tech campus environment. We view this problem from three complimentary prisms: situational awareness, security control, and emergency response management. In other words, a safe and open campus environment can be realized through a decision support system that enables the creation of a common operating picture (COP) of the campus environment shared by all campus entities (i.e., situational awareness). Having a COP of what goes on campus at any point in time is key for law enforcement personnel to put in place effective security control measures. Finally, common situational awareness and deliberate security control lay the foundation for an efficient and effective emergency response in the case of an emergency.

Figure 2 : Elements of safety in open campuses

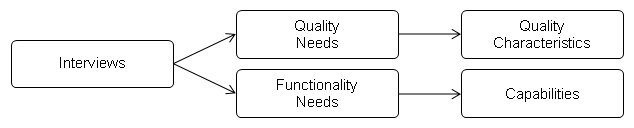

We elicit SINERGY capabilities by interviewing stakeholders who have expertise regarding campus safety and find initiatives to campus safety as critical. Virginia Tech’s resources (students, staff, faculty, campus structure, and existing systems) provided the context for these interviews. The context of the study helped us focus on understanding the problem domain and deriving key capabilities and quality attributes. Figure 3 illustrates the process through which the capabilities and quality attributes were identified. In addition, this phase was guided by the opinions of subject matter experts (SMEs) in related technologies and research areas. Finally, our study was complimented by participating in the Incident Command System (ICS) training program offered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Emergency Management Institute. This program provided us with the understanding of best practices in emergency management, and the legal constraints that guide these practices. Our objective was to conceptualize practice to guide GDSS design for campus safety, so that the systems facilitate coordination and response in a real-time decision-making context that characterize emergency response situations.

Figure 3: Elicitation process of capabilities and quality attributes

Table 1 shows a list of SINERGY stakeholder categories. We interviewed a number of representatives from each of the categories listed as indicated by the number next to the stakeholder category. The interviews focused on the capabilities that SINERGY should provide as a potential solution to current security and emergency management challenges from their perspective.

Stakeholder Category |

Examples |

|

|---|---|---|

Administrators (4) |

University president, vice president, dean, department chair |

|

|

Faculty, staff, students, campus visitors |

|

|

University police, town police, residence hall directors/assistants |

|

|

Firefighters, hospital staff, university emergency staff, health center staff |

|

|

Wireless sensor network researchers, autonomous systems researchers, information management researchers, social media researchers, sociologists |

Educational institutions, as any large enterprise, must comply with state and federal regulations in the preparation for emergencies and establishment of contingency plans for responding to threats that could harm personnel, faculty, students, and/or property. They are required to establish an Emergency Management office that works in tandem with other university offices to create response plans to emergencies not only for the short term but also for the long term. The director of this office serves as the campus emergency response manager in case of an incident involving the university.

Educational institutions should also comply with the Incident Command System (ICS), which is FEMA’s recommended emergency management framework that guides response plans to emergencies. Within this system, the director of the Emergency Management office serves as the Incident Commander (IC) and is responsible for assembling and managing all the agencies that need to collaborate in response to an incident.

Based on the interviews conducted with SINERGY stakeholders, a list of functionality needs have been identified. These functionality needs are specified in terms of capabilities. A capability is a broader concept than a requirement, and refers to what a system provides without detail about how it provides it. Formally, a capability is defined as “the ability to achieve a desired effect under specified standards and conditions through combinations of means and ways to perform a set of tasks."

This list in Table 2 is not intended to be exhaustive but covers the overarching needs expressed by more than one stakeholder. The list represents a starting point for the identification of SINERGY capabilities. Each need represents a high-level specification of a capability or a set of capabilities that the stakeholders would like SINERGY to provide. These needs are grouped by the three components of SINERGY main goal: security control, situational awareness, and emergency response management.

| Security Control | |

1 |

Diverse incident detection capabilities |

2 |

Diverse incident reporting capabilities |

3 |

On-demand surveillance capabilities |

| Situational Awareness | |

4 |

Common operational picture capabilities |

5 |

Geographical Information System and campus visualization capabilities |

6 |

Audible situational awareness capabilities |

7 |

Visual situational awareness capabilities |

8 |

Electronic text situational awareness capabilities |

| Emergency Response Management | |

9 |

Direct communication with emergency response personnel capabilities |

10 |

Response coordination capabilities |

11 |

Documentation capabilities for decisions, expenses, and damages |

12 |

Training capabilities for personnel and public |